By Peter Dula

The topic for this panel is Religious Perspectives on Human Development. My remarks could perhaps be characterized as something like Development Perspectives on Religion. "Development is a term of movement. To develop means to move from one place, the under- developed or less developed, to the more developed. So it is also a term of judgment. The language suggests that it is a movement from bad to good, or at least from less good to more good. How we understand those two places is extremely important and is determined by a great many assumptions about history, what it is and how it is told. So I will begin broadly with a book about how history is written that was published about five years ago by the Indian postcolonial theorist, Dipesh Chakrabarty called “Provincializing Europe”.

The "Europe" in Chakrabarty's title is not the landmass north of the Mediterranean, it is the political structures and that we have come to identify as modern the nation state, bureaucracy, and capitalist enterprise- structures that were never just European, and which now are global. He writes, it is impossible to think of anywhere go deep into the intellectual and even theological traditions of Europe (Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 4 Italics in original. All further references will be noted parenthetically in the text). Chakrabarty means the way that histories of non – Western Nations are written as variations on a master narrative called 'the history of Europe'. History means a certain linearity of progress in which Europe is always the 'now' to the non Europe's not yet'. It is the modern to the traditional, the rational to the superstitious. It is the developed in 'underdeveloped'. History consigns the non- Western world to what Chakrabarty calls 'the waiting room of history', and in doing so it converts history itself into a version of this waiting room. He doesn't mean the waiting room of a doctor's office. He means the waiting room at a train station.The train is going one direction. Its path is determined by the steel rails on which it rides. 'We were all headed for the same destination' (8).The master narrative assumes that the trajectory of European history- the transition narratives which trace the development from feudalism to capitalism, from medieval to modern, despotic to constitutional, from underdeveloped to developed- can be mapped onto the history of say, Jordan or Lebanon or Iraq or India. Non- Western countries may have their own stories, but they are always subplots within the larger story. Within this larger story, the overriding themes are development, modernization and capitalism. Such histories are ones of absence and failure, lack and inadequacy. The failure to form a Western- style state, the inadequacy of the people to be democratic.Various historians place the blame in various places. For colonial historians the 'native' was the figure of lack, requiring a period of British or French education in order to be made ready for the end of history, citizenship and the nation- state. For the nationalist historians, the blame was shifted and the figure of lack became the peasant. In Jordan, for example, it is the Bedu who are this figure of lack. Or take the example of Iraq, Dexter Filkins, who has been reporting for the New York Times from Iraq since the invasion, wrote on Oct. 30 of this year, 'Two and half years later, it’s clear that a large percentage of Iraqis were either too traumatized or too tangled up in their traditions to grasp a democratic future'. The point is not to say whether this is true of Iraqis or not. Engaging in that argument would only make Chakrabarty's point, that this is the standard. That Iraqis can't be judged on their own merits, but only in term of how they measure up to their 'democratic future' with all that implies.

'Traditions' in the NYT quote may mean a lot of things. But one thing that it almost always means is 'religion'. We could read it as saying, 'A large percentage of Iraqis were too caught up in their religion to grasp a democratic future'. Essential to and inseparable from this master narrative of modern progress, is a deeply ingrained narrative of religious progress. Immanuel Kant, the greatest of the philosophers of the Western enlightenment, wrote, "A historical faith attaches itself to pure religion as its vehicle, yet, if there is a consciousness that this faith is merely such and if, as the faith of a church, it carries a principle for continually coming closer to pure religious faith until finally we can dispense of that vehicle, the church in question can always be taken as the true one (Religion Within the Bounds of Mere Reason p. 122)dgh'.

When Kant says 'a historical faith' he means those particular sets of doctrines and practices we know as religions. When he says pure religion he means an individualist, inward experience of the heart. There are at least three claims being made in this one sentence. First, that there is one and only one 'pure religion' and it is tangled up with various expendable 'vehicles' called Judaism, Islam, Christianity, etc. Think of it like a cob of corn. The pure religion is the kernel obscured by the husks of doctrines, rituals, etc. Second, what counts as progress in religion is the gradual evolutionary shedding of the husk, getting down to the pure, undiluted religion. Third, the community that is closest to pure religious faith, closest to being able to dispense with the vehicle, is modern liberal Protestantism. (At least it was in the late 18th century when Kant was writing. Nowadays it is Secularism, the new religion of the West according to Pope Benedict XVI).

To get back to Chakrabarty's terms, anything less than Secularism is the 'lack' that must be filled, the 'incomplete' that must be completed' (Kant again, 'we cannot expect to draw a universal history of the human race from religion on earth (in the strictest meaning of the word), for in as much as it is based on pure moral faith, religion is not a public condition, each human being can become conscious of the advances which he has made in this faith only for himself. Hence, we can expect a universal historical account only of ecclesiastical faith, by comparing it, in its manifold and mutable forms, with the one, immutable, and pure religious faith(p. 129)). Ranking the extent of the lack, the adequacy of the husks, became a task of 19th century anthropology. They spoke of higher and lower religions. The higher were the ones that most closely approximated what liberal Protestantism defined itself against, namely, Catholicism and Judaism and later Hinduism and Islam. The higher religions were those that most emphasized all those things as well as ritual, the saints, the priesthood. Here the case of Buddhism is very interesting. The Buddha comes to be understood as an Indian Martin Luther and Buddhism and Hindu Protestantism (Richard King, Orientalism and Religion: Postcolonial Theory, India and 'The Mystic East', (London: Routledge, 1999), p. 144-145). But distinctions were also made within religions. The 19th century orientalists were enamored with Theravada Buddhism much more than with Mahayana Buddhism. Sufi Islam is so much more acceptable than Shi'a Islam. Sufis are 'mystical' while the Shi'a are religious with their veneration of Ali and Hussein and the rituals and iconography that brings with it. Take, for example, the popularity of Rumi in the West. This 13th century Sufi mystic was the best- selling poet in the US in the 1990s. but the millions who bought and read his poetry had no idea that for most of his life Rumi taught Sharia law at a Madrasa. And they couldn't care. His poetry, if not his theology, according to those American readers, sheds the husks of Islam and approaches pure religion. (That is, it does so if you don't know what you are looking for).

So far I have spoken of two grand narratives, two accounts of the waiting room of history, the political and the religious. But they are not two different narratives. They are aspects of the one narrative. How so? Both are essential to that hallmark of political liberalism, the separation of religion and state, Religion is always an object of fear. It is the thing which must be gotten out of the road of the march of progress. An example from Iraq will help to show how this works. A detailed thirty page proposal from UNOPS (United Nations Office for Project Services) in May of 2004 called for a vast national democratic dialogue and spoke of inviting academics, journalists and NGO workers'.

There was not a word about religious leaders, and when I pushed the author of the proposal to account for this, she told me that religion is private'. She has a graduate degree from a very good American political science department). A certain account of religion is simply taken for granted by those with power in what gets called the 'international community'.

Such a claim is understandable in the west where it was invented and where, for many, religion often is as private as Kant wanted it to be. In Iraq it is just silly. The better argument, which I think the UNOPS claim is a cover for, is that religion in Iraq is public, way too public, and part of the point of spreading 'democracy' to it is to contain Islam by educating Muslims, especially the poor, uneducated, rural Muslims, to privatize their convictions.

But is that so bad? Isn't a secular state with only a minima; role for religion the best thing for Iraq? Well, I confess I think so. It seems obvious that the struggle for social justice requires something like these narratives. But then the question is, do I think that because it is true, or because, as an overeducated American, I lack the imagination necessary to escape the categories of political modernity? That, I think, is Chakrabarty's claim. His argument is not so much that the master narrative of Europe is 'bad' or 'wrong'. His point, rather, is to awake us to its enormous power. He is not offering us a good and right alternative to the bad and wrong. That is part of the point. If there were readily available alternatives then the narrative wouldn't be that powerful. A sign of its power is that its explanatory scope is so extensive that it cuts off the imagination before it even gets started.

What could it mean to expand our imaginations? Chakrabarty proposes that we begin by re-narrating those points of lack. He writes, "let us begin from where the transition narrative ends and read "plenitude" and "creativity" where this narrative has made us read "lack" and "inadequacy" (34-35). The problem, recall, is that it has become impossible to think without certain categories, impossible to know if those categories are helpful or not unless we make the imaginative leap of thinking outside them. It is those categories themselves which force us to see 'modernity' as inevitable, that blind us to other modes of engaging the world. It is those categories that imprison the imagination instead of liberating it.

Can the aid agencies and development agencies help with that task? Can the international NGOs help with that task? The answer is by no means clear. The NGOs have come a long way in the last few decades. They have become, or tried to become, more sensitive to local populations. They have discovered things like appropriate technology and conflict resolution. They have tried to work more conversationally. They try not to assume that they are coming with the answers but instead are coming to discern answers in dialogue with local populations. Yet they seem to be under more criticism than ever before. A widely read recent text on globalization calls the NGOs 'the mendicant orders of global capital' (Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000)). That is, they are to globalization what the wandering monks of the middle ages were to the Holy Roman Empire.

Can the local NGOs help with this task? Again, the answer is not entirely clear. In Iraq, unlike Lebanon or Palestine, the NGO is a very new thing, so MCC, some other international NGOs and UNDP did a lot of work to train local NGOs. We did this because we thought that Iraqi NGOs would do a much better job than we could because Iraq is their country, their people. And of course that is true. But what I quickly realized is just how much the NGO is a western invention and therefore how much a UN workshop is training in how to become western.

Can religious NGOs help with think tasks? I certainly hope so. Mennonite Central Committee works with the Imam Sadr Foundation for many reasons. One is that we think it does very good work. But another is that we want you to pry open our western imaginations. But again, a general answer to this question is not entirely clear. To say why, let me give an example from the US context. Early in his first term, George Bush announced a policy that he called support for 'faith- based initiatives'. That is, he proposed to increase the amount of money given to religious charities. The religious NGOs were very excited and lined up like panting dogs to get their share. MCC was one of the very few who refused because we have a policy against taking any money from the American government. But the question of whether to accept money from the US gov't was just one question. The other was, 'if the American empire likes what we are doing, shouldn't that suggest that we are doing something wrong?'

The lack of clarity in all these instances is due to a great extent to the closeness of the NGOs to the institutions of political power in our world. NGOs, aid agencies, development groups, always say they work for the poor. But if you look closely it can seem like they are just employees of governments, the UN, the institutions of global finance like the World Bank and IMF.

There is a story repeated twice in the Christian scriptures, in both the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke. It is of Jesus' temptation in the desert. Before the beginning of his ministry Jesus goes out into the wilderness. He fasted there for 40 days and nights and at the end of those forty days the devil came to him and led him up on a mountain and showed him all the kingdoms of the world. The devil said to Jesus, 'To you I will give their glory and all this authority; for it has been given over to me, and I give it to anyone I please'. And Jesus refused saying 'It is written, worship the Lord your God and serve him only'. Jesus could have been a king. He would have been a better king than the Roman emperor. A better king than George Bush or Kofi Annan. He could have done a lot of good things. He would have cared for the poor and not just the rich. He would have helped the farmers and not just the business people. But he doesn't do it. He walks down off the mountain back into a life of poverty that ends in a bloody martyrdom. It is this direction that Christians are called to follow. But the history of the church, as I don't need to tell you, has been a history of refusing this example. It is a history, since Emperor Constantine in the 4th century, of priests holding hands with kings, of Christians taking up swords and guns, making crusades in the name of God or of country or of democracy, usually not knowing the difference.

But the true church, the repentant church, will always try to go the other way, away from power and kingship and towards the poor, what scripture calls 'the least of these'. But I don't think it is just a story for Christians. It is also a story for development agencies. Many of you here work for such agencies. And if you, do you know that you are always forced to look in two directions. On one hand, there are the poor and the oppressed that you want to help. On the other, are the institutions of power from whom you get your money and to whom you must report. The place where our imaginations will be expanded will be with the poor, not with the powerful.

التاريخ، الدين والمنظمات الأهلية

بيتر دولا

موضوع هذه الجلسة هو النظرات الدينية للتنمية البشرية. ويمكن وصف ملاحظاتي ربما بأنها نظرات تنموية عن الدين. "التنمية هي لفظة تعني التحرك. وضع سبل للتحرك من مكان، المتخلف أو الأقل تطورًا، إلى مكان آخر هو أكثر تطوراً. إنها إذاً لفظة تعني الحكم. لغوياً، تعني اللفظة تحركاً من السيء إلى الجيّد، أو على الأقل من الأقل جودةً إلى الأكثر جودةً. وترتدي كيفية فهمنا لهذين المكانين أهمية قصوى وتحددها افتراضات متعددة حول التاريخ، وماهيته وكيفية تلاوته. لذا سوف أبدأ بتفسير عام انطلاقاً من كتاب عن كيفية كتابة التاريخ نشره منذ خمسة أعوام المنظِّرُ الهندي ما بعد الاستعماري ديبيش شاكرابارتي وكان بعنوان "تحويل أوروبا إلى محافظات".

و"أوروبا" في عنوان شاكرابارتي ليست كتلة اليابسة التي تقع شمال المتوسط، بل هي البنى السياسية التي اعتبرناها عصرية – الدولة الأمة، والبيروقراطية، والمبادرة الرأسمالية – وهي بنى لم تكن يوماً أوروبية حصراً، بل وهي اليوم عالمية. ويقول الكاتب إنه من المستحيل التفكير في أي مكان آخر يمكن الغوص فيه في التقاليد الفكرية وحتى اللاهوتية لأوروبا (ديبيش شاكرابارتي، تحويل أوروبا إلى محافظات (برنستون: مطبوعات جامعة برنستون، 2000). سوف يشار إلى كافة المراجع بين هلالين لاحقًا في النصّ). ويعني شاكرابارتي بذلك الطريقة التي يُكتَب فيها تاريخ الأمم غير الغربية كمتغيرات بالنسبة إلى نموذج سرديّ أساسيّ يُدعى "تاريخ أوروبا". والتاريخ يعني نوعاً من الخطّيّة في التقدم تشكل فيه أوروبا دائمًا "الآن" مقابل الـ "ليس بعد" في غير أوروبا. إنه العصري مقابل التقليدي، العقلاني مقابل الخرافي. إنه المتطور مقابل "المتخلف". ويحصر التاريخ العالم غير الغربي بما يصفه شاكرابارتي بـ"غرفة انتظار التاريخ"، وبهذا يحول التاريخ بحد ذاته إلى نسخة من غرفة الانتظار تلك. هو لا يعني بها غرفة الانتظار في عيادة طبيب. بل يعني غرفة الانتظار في محطة قطار. والقطار يسير في اتجاه واحد. وطريقه تحددها السكك الحديد التي يسير عليها. "كنا جميعاً سائرين في الاتجاه نفسه" (8). ويفترض النموذج السردي الأساسي بأن مسار التاريخ الأوروبي – النماذج السردية الانتقالية التي ترسم التطور من الإقطاعية إلى الرأسمالية، ومن جاهلية القرون الوسطى إلى العصرانية، ومن الاستبدادية إلى الدستورية، ومن التخلف إلى التطور – يمكن إدخاله في خارطة تاريخ الأردن، أو لبنان أو العراق أو الهند مثلاً. وقد يكون للبلدان غير الغربية قصصها الخاصة بها، لكنها تشكل دائمًا الحبكة الفرعية ضمن القصة الأكبر. ومن ضمن هذه القصة الأكبر، تبرز التنمية والتحديث والرأسمالية كمواضيع سائدة. وتعتبَر هكذا تواريخ تواريخ، غياب وفشل، نقص وعدم مواءمة. الفشل في تشكيل دولة على الطراز الغربي، وعدم مواءمة الشعب ليكون ديموقراطياً. وتتنوع مواضع اللوم مع تنوع المؤرخين الذين يلقونه. فبالنسبة إلى المؤرخين الاستعماريين كان "المواطن الأصلي" صورة للنقص، وبحاجة إلى فترة من التربية البريطانية أو الفرنسية لكي يصبح جاهزًا لنهاية التاريخ، والمواطنية، والدولة الأمة. أما المؤرخون القوميون، فيحولون اللوم وأصبح النقص متمثلاً في الفلاح. ففي الأردن مثلاً، كان البدو صورة النقص. أو لنأخذ مثل العراق، ونستذكر ما كتب ديكستر فيلكنس الذي كان صحافيًا للنيويورك تايمز في العراق منذ الاجتياحوذلك بتاريخ 30 تشرين الأول/أكتوبر، "بعد سنتين ونصف السنة، من الواضح أن نسبة كبيرة من العراقيين كانوا إما مصابين بصدمة جارحة كبيرة أو عالقين إلى حد كبير في شباك تقاليدهم فهم غير قادرين على استيعاب مستقبل ديموقراطي". وليست المسألة هنا أن نقول ما إذا كان هذا صحيحاً عن العراقيين أم لا. لكن الخوض في اعتماد هذه الحجة يجعل من رأي شاكرابارتي الرأي المعيار. أي أن العراقيين لا يمكن الحكم عليهم بحسب ما يستحقونه بل فقط بمدى استحقاقهم لـ"مستقبلهم الديموقراطي" مع كل ما يعنيه.

وقد ترتدي كلمة "تقاليد" الواردة في الاقتباس من مقالة النيويورك تايمز معاني كثيرة. لكن المعنى الدائم تقريباً يبقى "الدين". فيمكن قراءة الاقتباس كما يلي: " إن نسبة كبيرة من العراقيين كانوا عالقين إلى حد كبير في شباك تقاليدهم فهم غير قادرين على استيعاب مستقبل ديموقراطي". فنرى عنصراً ضرورياً ولا يمكن فصله عن هذا النموذج السردي الأساسي للتقدم العصري هو نموذج سردي للتقدم الديني مترسّخ بعمق. فقد كتب "إمانويل كانط" كبير فلاسفة عصر الأنوار الغربي قائلاً "إن القدر التاريخي يربط نفسه بالدين الصرف كناقل له، ولكن إذا ساد وعي بأن القدر هو مجرد هذه الحالة وإذا كان يحمل، كإيمان الكنيسة، مبدأ للاقتراب باستمرار من الإيمان الديني الصرف إلى حين نتمكن في النهاية من الاستغناء عن وسيلة النقل تلك، فإن الكنيسة المعنية يمكن أن تعتبَر دائماً أنها الكنيسة الحقة" (الدين ضمن حدود المنطق الصرف، ص. 122).

عندما يقول كانط "إيمانًا تاريخياً" يعني مجموعات العقائد والممارسات الخاصة تلك التي نعرفها كأديان. وعندما يقول الدين الصرف يعني تجربة فردية داخلية قلبية. ففي هذه الجملة الواحدة ثلاثة ادعاءات على الأقل. أولاً، أن ثمة ديناً صرفاً واحداً وحيداً وهو عالق في شباك "وسائل نقل" قابلة للتوسع تسمى اليهودية، والإسلام، والمسيحية، إلخ. إنه كقَولَحة ذُرة. فالدين الصرف هو اللب الذي تغطيه قِشَر العقائد، والطقوس، إلخ. ثانيًا، ما يهم في التقدم في الدين هو ذاك التظليل التطوري التدريجي للبّ، حتى الوصول إلى الدين الصرف، غير المخفَّف. ثالثًا، إن الجماعة التي تعتبَر الأقرب إلى الإيمان الديني الصرف، الأقرب إلى القدرة على الاستغناء عن وسيلة النقل هي البروتستانتية الليبرالية العصرية. (أقله جاءت كتابة "كانط" هذه في أواخر القرن الثامن عشر. أما في أيامنا فهي العلمانية، وهي الدين الجديد للغرب حسب وصف البابا بندكتوس السادس عشر).

بالعودة إلى تعابير شاكرابارتي، أي شيء أقل من العلمانية هو "النقص" الذي يجب ملؤه، "العديم الاكتمال" الذي يجب إكماله (مجددًا كانط "لا يمكننا أن نتوقع استخلاص تاريخ كوني للبشر من الدين على الأرض (بالمعنى الصرف للكلمة)، إذ إن الدين، بقدر ما هو مرتكز على الإيمان المعنوي الصرف، فهو ليس شرطًا عاماً، فكل كائن بشري يستطيع أن يصبح واعيًا للتقدمات التي أحرزها في إيمانه فقط لنفسه. بالتالي، يمكننا أن نتوقع حساباً تاريخياً كونياً فقط للإيمان الكنسي، بمقارنته بأنماطه وأشاكله المتعددة بالإيمان الديني الصرف وغير القابل للتحول. (ص. 129)). وأصبح ترتيب درجات النقص، وعدم مواءمة القِشَر، مهمة علم الأنثروبولوجيا في القرن التاسع عشر. فقد حُكي عن أديان أعلى وأدنى. فالأديان الأعلى هي التي تقترب أكثر من غيرها مما حددته البروتستانتية الليبرالية لنفسها ضد الكاثوليكية واليهودية ولاحقاً الهندوسية والإسلام. والأديان الأعلى هي تلك التي تركز أكثر من غيرها على تلك الأمور كلها كما على الطقوس، والقديسين، والكهنوت. وهنا تعتبَر حالة البوذية في غاية الأهمية. فالبوذية تُفهم كاللوثرية الهندية والبوذية كالبروتستانتية الهندوسية (Richard King, Orientalism and Religion: Postcolonial Theory, India and 'The Mystic East', (London: Routledge, 1999), p. 144-145). لكن بعض التمايزات قد برزت ضمن الأديان. فالمستشرقون في القرن التاسع عشر قد تُيّموا ببوذية التيرافادا أكثر من بوذية الماهايانا. وإسلام الصوفية مقبول أكثر بكثير من إسلام الشيعة. فالصوفيون "متصوفون" بينما الشيعة دينيون بتبجيلهم لعلي والحسين مع الطقوس والإقونوغرافيا (الرمزية او القدسية) التي ترافق ذلك. لنأخذ مثلاً، شعبية الرومي في الغرب. فهذا المتصوف الصوفي في القرن الثالث عشر كان أكثر الشعراء شهرة في الولايات المتحدة في التسعينيات لكن الملايين الذين كانوا يشترون أو يقرأون شعره لم يدركوا أن الرومي قد درّس معظم حياته الشريعة الإسلامية في إحدى المدارس الشرعية. ولم يكونوا ليأبهوا بذلك. فشعره، إن لم يكن لاهوته، برأي أولئك القراء الأميركيين، كان يرمي بقشور الإسلام ويقترب من الدين الصرف. (أي أنه يؤدي إلى ذلك في حال لم تدرِك ما أنت ساعٍ إليه).

حتى الآن تحدثت عن نموذجين سرديين كبيرين، عن حسابين لغرفة انتظار التاريخ، السياسي والديني. لكنهما ليسا بالنموذجين السرديين المختلفين. بل هما جانبان من نموذج سردي واحد. كيف؟ كلاهما ضروريان لدمغة الليبرالية السياسية تلك، أي الفصل بين الدين والدولة، فالدين هو دائماً موضوع خوف. إنه الشيء الذي يجب إزالته عن طريق مسيرة التقدم. ونأتي بمثل من العراق لإظهار كيفية حصول ذلك. دعا اقتراح مفصل من ثلاثين صفحة لمكتب الأمم المتحدة لخدمات المشاريع (UNOPS) في ايار/مايو 2004 إلى حوار ديموقراطي وطني واسع وتحدث عن دعوة أكاديميين، وصحافيين وناشطين في المنظمات الأهلية.

لم ترد كلمة واحدة عن الزعماء الدينيين، وعندما حثثت واضعة الاقتراح وهي حائزة شهادة عالية من كلية علوم سياسية أميركية بارزة على تبرير ذلك، قالت لي إن الدين أمر خاص.. وإن حساباً معيناً للدين يعتبَر أمراً مفروغاً منه من جانب مَن هم في السلطة في ما يسمّى "الأسرة الدولية".

ويمكن تفهم هكذا ادعاء في الغرب حيث ابتُكِر وحيث يعتبر كثيرون الدين أمراً خاصاً بقدر ما أراده "كانط" أن يكون كذلك. لكن في العراق الأمر سخيف. فالحجة الأفضل، التي برأيي يشكل ادعاء مكتب الامم المتحدة لخدمات المشاريع UNOPS غطاء لها، هي أن الدين في العراق أمر عام، عام إلى حد كبير، ومن عناصر نشر "الديموقراطية" فيه، احتواء الإسلام من خلال تعليم المسلمين، خاصة المسلمين الفقراء، وغير المتعلمين والريفيين في سبيل خصخصة قناعاتهم.

لكن هل هذا الأمر سيئ؟ أليست دولة علمانية بتأثير أدنى للدين أفضل حل للعراق؟ أعترف بأني من هذا الرأي. إذ يبدو واضحاً أن الكفاح من أجل العدالة الاجتماعية يستلزم شيئاً مماثلاً للنماذج السردية هذه. لكن السؤال الذي يبرز هو ما إذا كنت أعتقد ذلك لأنه صحيح أم لأني، بصفتي أميركياً مفرط التعلّم، أفتقر إلى الخيال الضروري لأفلت من تصانيف الحداثة السياسية؟ هذا باعتقادي ادعاء شاكرابارتي. وحجته ليست أن النموذج السردي الأساسي لأوروبا هو "سيء" أو "خاطئ". بل غايته أن يجعلنا نعي سلطته العظيمة. فهو لا يعرض علينا بديلاً جاهزًا جيداً وصحيحاً للسيئ والخاطئ. فهذا جزء من نظرته. فلو كان للبدائل الجاهزة وجود لما كان النموذج السردي بهذه القوة. ومن مؤشرات قوته أن نطاقه التفسيري متّسع إلى حد يقطع الخيال قبل أن ينطلق حتى.

ما معنى أن نوسّع خيالاتنا؟ يقترح شاكرابارتي أن نبدأ بإعادة سرد نقاط النقص تلك. فهو كتب "لنبدأ من حيث ينتهي السرد الانتقالي ونقرأ "كمالاً" و"إبداعاً" حيث جعلنا هذا السرد نقرأ "نقصاً" و"عدم مواءمة" (34-35). ولا ننسى أن المشكلة أنه أصبح من المستحيل التفكير من دون بعض التصانيف. من المستحيل أن نعرف إن كانت تلك التصانيف مفيدة أم لا إلا إذا قمنا بالقفزة الخيالية للتفكير خارجها. إنها تلك التصانيف نفسها التي تدفعنا إلى رؤية "الحداثة" كأمر لا مفر منه، وتعمينا عن أنماط أخرى لخوض العالم. إنها تلك التصانيف التي تحبس الخيال بدلاً من إطلاقه.

هل باستطاعة وكالات المساعدة والتنمية أن تساعد على تحقيق هذه المهمة؟ هل باستطاعة المنظمات الأهلية أن تساعد على تحقيق هذه المهمة؟ ليس الجواب واضحاً. فالمنظمات الأهلية سلكت طريقاً طويلاً في العقود القليلة الماضية. فقد أصبحت، أو حاولت أن تصبح، أكثر اهتماماً بالسكان المحليين. فقد اكتشفت أموراً كالتكنولوجيا المناسبة وفض النزاعات. وحاولت أن تعمل بواسطة المزيد من التحاور. وتحاول ألا تفترض أنها تأتي بأجوبة جاهزة بل تأتي لتكتشف الأجوبة في الحوار مع السكان المحليين. لكنها تبدو عرضة للانتقاد أكثر من أي وقت مضى. فيصف نص حديث شهير حول العولمة المنظمات الأهلية بأنها "الأوامر المستجدية لرأس المال العالمي" (Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000)). أي أنها تؤدي في العولمة الدور الذي كان للرهبان المتجولون في القرون الوسطى في الامبراطورية الرومانية المقدسة.

وهل باستطاعة المنظمات الأهلية المحلية أن تساعد على تحقيق هذه المهمة؟ مجدداً الجواب ليس بواضح. ففي العراق، وبعكس لبنان وفلسطين، تشكل المنظمة الأهلية حالة جديدة جداً، لذا فإن اللجنة المركزية المانونية (MCC)، وبعض المنظمات الأهلية الدولية الأخرى وبرنامج الأمم المتحدة الإنمائي قد قامت بعمل كثير لتدريب المنظمات الأهلية المحلية. وقمنا بذلك لأننا اعتقدنا أن المنظمات الأهلية العراقية كانت لتقوم بعمل أفضل بكثير من العمل الذي قد نقوم به لأن العراق هو بلدها وشعبها. وهذا صحيح طبعاً. ولكن ما وعيته بسرعة هو مدى كون المنظمة الأهلية ابتكاراً غربياً وبالتالي مدى كون ورشة عمل للأمم المتحدة تقوم بالتدريب على اعتناق الطابع الغربي.

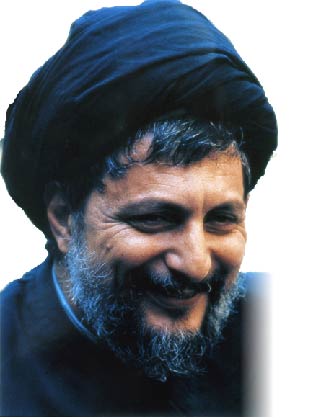

هل باستطاعة المنظمات الأهلية الدينية أن تساعد على تحقيق هذه المهام؟ آمل ذلك فعلاً. فاللجنة المركزية المانونية تعمل مع مؤسسات الإمام موسى الصدر لأسباب متعددة. أحدها أننا نعتقد أنها تقوم بعمل ممتاز. والسبب الآخر أننا نريدكم أن تطلقوا العنان لخيالاتنا الغربية. ولكن مجدداً أقول إن جواباً عاماً عن هذا السؤال ليس واضحاً كلياً. لأشرح ذلك دعوني أعطي مثلاً من الإطار الأميركي. في بداية عهد الرئيس بوش، أعلن عن سياسة دعاها سياسة الدعم "للمبادرات الإيمانية". أي أنه اقترح زيادة مبلغ المال الذي يقدَّم للأعمال الخيرية الدينية. ففرحت المنظمات الأهلية الدينية واصطفت كالكلاب الجائعة لتنال حصتها. وكانت اللجنة المركزية المانونية من بين المنظمات القليلة جدًا التي رفضت لأن السياسة التي نعتمدها ترفض قبول اي مال من الحكومة الأميركية. لكن السؤال حول ضرورة قبول المال من الحكومة الأميركية أم لا كان سؤالاً واحداً. أما السؤال الثاني، فهو التالي "إن كانت الامبراطورية الأميركية تحب ما نفعله، ألا يفترض ذلك أننا نقوم بعمل خاطئ؟"

وانعدام الوضوح في هذه الأمثلة كافة عائد إلى حد كبير إلى اقتراب المنظمات الأهلية من مؤسسات السلطة السياسية في عالمنا. فالمنظمات الأهلية، ووكالات المساعدة، والمجموعات التنموية، تقول دائماً إن عملها هو للفقراء. ولكن إذا نظرت عن كثب إليها قد تبدو كأنها مجرد موظَّفين في الحكومات، في الأمم المتحدة، والمؤسسات المالية العالمية مثل البنك الدولي وصندوق النقد الدولي.

ثمة قصة ترد مرتين في الكتب المقدسة المسيحية، في إنجيل متى كما في إنجيل لوقا. إنها قصة تجارب المسيح في الصحراء. فقبل أن يبدأ خدمته خرج يسوع إلى البرية. وصام 40 يوماً وليلة وعند انتهاء تلك الأيام الأربعين جاءه الشيطان واقتاده إلى أعلى جبل وأراه ممالك الدنيا. فقال الشيطان للمسيح "أعطيك هذا المجد وهذه السلطة إن جثوت لي ساجداً؛ إذ أعطي هذا كله لي وأنا أعطيه لمن أريد". فرفض يسوع قائلاً له "إنه مكتوب، للرب إلهك تسجد وإياه وحده تعبد". لكان باستطاعة يسوع أن يصبح ملكاً. كان ليصبح ملكاً أفضل من الامبراطور الروماني. ملكاً أفضل من جورج بوش أو كوفي أنان. لكان حقق أموراً خيرة كثيرة. لكان اهتم بالفقراء وليس فقط بالأغنياء. لكان ساعد المزارعين وليس أصحاب الأعمال فقط. لكنه لم يقبل. بل نزل من على الجبل عائداً إلى حياة فقر انتهت بشهادة دموية. هذا هو الاتجاه الذي يُدعى المسيحيون إلى سلوكه. لكن تاريخ الكنيسة، ولا داعي لأن أذكركم به، كان تاريخاً رفض هذا المثل. إنه تاريخ تميز، منذ الامبراطور قسطنطين في القرن الرابع ميلادي، بكهنة يمسكون بأيدي الملوك، ومسيحيين يحملون السيوف والأسلحة، ويخوضون حروباً صليبية باسم الله أو الوطن أو الديموقراطية، وهم لا يدرون الفرق عادة.

لكن الكنيسة الحقة، الكنيسة التائبة، سوف تحاول دائماً أن تسلك الاتجاه الآخر، مبتعدةً عن السلطة والمَلَكية لتتجه نحو الفقير، ومن يسميهم الإنجيل بـ"صغار القوم". لكني لا أظن أن هذه القصة هي للمسيحيين فقط. إنها قصة للوكالات التنموية أيضاً. وكثيرون منكم هنا يعملون لتلك الوكالات. وفي هذه الحال تعرفون أنكم تجبرون دائماً على النظر في اتجاهين مختلفين. فمن جهة الفقراء والمضطهدون الذين تريدون أن تساعدوهم. ومن جهة أخرى مؤسسات السلطة التي تتلقون منها مالكم والتي عليكم إبلاغها بنتائج عملكم. أما المكان الذي سوف تتسع فيه خيالاتنا فسوف يكون مع الفقراء لا مع أصحاب السلطة.

ـــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ

تعقيب سماحة الشيخ الزين

شكراً للدكتور بيتر دولا. وأحب أن أعقّب تعقيباً قصيراً باختصار هو أننا لن ندخل في الخلافات بين المذاهب المسيحية أولاً، ولا بين المذاهب الاسلامية. لنلتقي جميعاً على ما درج عليه الامام موسى الصدر من خط انساني مضيفاً الى ما تفضّل به الاخوان الاعزاء الى اننا جميعاً مع الاختلافات في الرأي إلا أننا نجمع على قضية واحدة وأساسية هي أن جميع هذه الشرائع تهدف الى خدمة الانسان، والى تكريم الانسان والى هذا التكريم الذي هو تكريم كوني وانساني. ألفت انتباهكم الى ما ورد في القرآن الكريم حيث يقول تبارك وتعالى:"﴿ألم تروا أن الله سخّر لكم ما في السموات وما في الارض وأسبغ عليكم نعمه ظاهرة وباطنة﴾. هذا الانسان المخلوق بين الخلائق، سخّر له الكون في خدمته، ثمّ أعقب ذلك ووضع المثل الأعلى في تكريم الانسان: ﴿وإذ قال ربك للملائكة إني جاعل في الارض خليفة﴾، رفعه الى اعلى المستويات بين سائر الخلائق وجعله خليفة له على هذه الارض، وأكّد هذه الخلافة بالسلوك وفي الواقع حينما قال: ﴿ولقد كرّمنا بني آدم﴾ ونحن جميعاً وان اختلفت التفصيلات والآراء نلتقي على تكريم الانسان لنقول ان على الدولة بتشريعاتها ، بالقوانين وبالتشريعات وبسائر الوزارات عليها ان تعمل على تكريم الانسان وخدمته. الفنون والعلوم وسائر النشاطات الإنسانية يجب ان تتوجه هذا التوجه في خدمة الانسان كما وجّه الله تبارك وتعالى الكون لخدمته. فالمجتمعات البشرية عليها ان تتوجه لخدمة هذا الانسان وتكريمه، لنصل الى محظور هل من تكريم الانسان السير في تكديس القنابل النووية؟ هل من تكريم الانسان ما نرى ونسمع من تدمير البيوت وتشريد للنساء والاطفال في فلسطين والعراق؟

فنلفت نظر العالم المتحضر في البلدان العربية وفي اوروبا وفي اميركا، ان توجهوا بالعلوم والاختراعات والتشريعات لخدمة هذا الانسان الذي كرّمه الله وسخّر من أجله ولخدمته السموات والأرض. هذا ما نُجمِع عليه جميعاً وإن اختلفت بيننا التفصيلات كما سمعتم.

والآن أترك المجال لمداخلات مبتدئاً بإخواني وبعدها نأتي اليكم, اذا أحب أحد من المحاضرين الكرام أن يتدخل برأي من الآراء مضيفاً الى ما قال، نحن الآن على أتمّ الاستعداد.